Case 14

- Influential Art Forms

Russell Laker, Anatomy of lettering. London: Studio Vista, 1965. SPRH 744.42 LAK

Hotere continued to be inspired by his fellow artists and their respective strengths throughout his career. The likes of Barry Cleavin, Marilynn Webb, Paratene Matchitt, and Marian Maguire were just a few who nurtured his interest in various artistic media. He eventually became known as much for his works using typically New Zealand materials such as corrugated iron, no. 8 wire, recycled timber, and lead-headed nails, as for his paintings on canvas. He punctuated many of his drawings and paintings with symbols, letters, and numbers. Sometimes, if not hand-written, he would use stencils, as for the Sangro series of 1962 and 1964. He began using lettering as part of his art while abroad, using ink or paint. Eventually he even took to crafting words on metal using a blowtorch, as in the Oputae Observation Point series (1989).

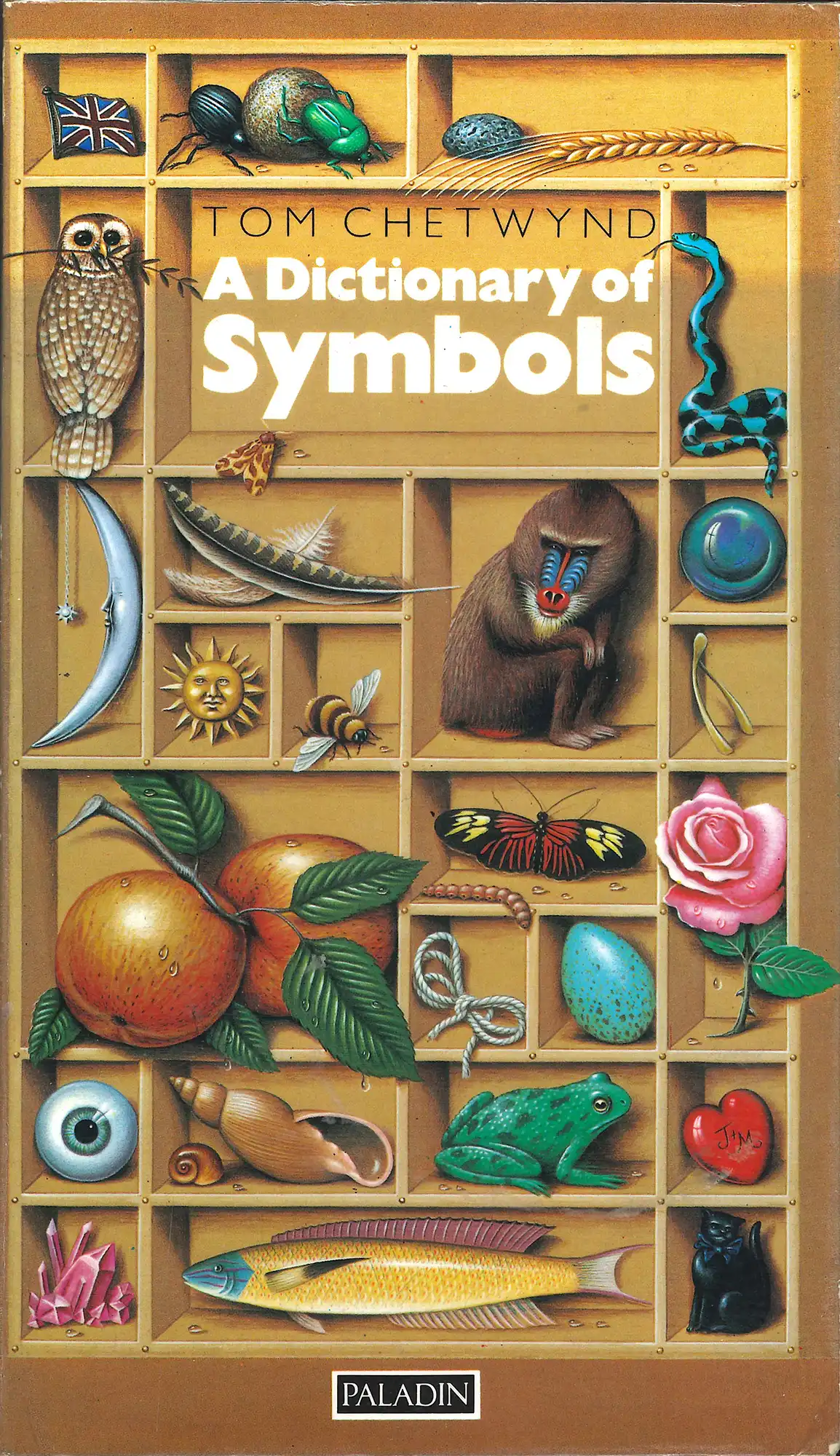

Tom Chetwynd, A dictionary of symbols. London: Paladin Grafton Books, 1987. SPRH 302.2223 CHE

Although Hotere resented the religious tuition foisted upon him at school, he nevertheless often incorporated traditional Catholic iconography into his work. Autobiographical themes recurring in his paintings included his faith, his family and the land, and he frequently used the cross (sometimes represented diagonally), or the heart and cross images. This Dictionary of Symbols was given to Hotere by Adair Bruce, with an inscription on the title page.

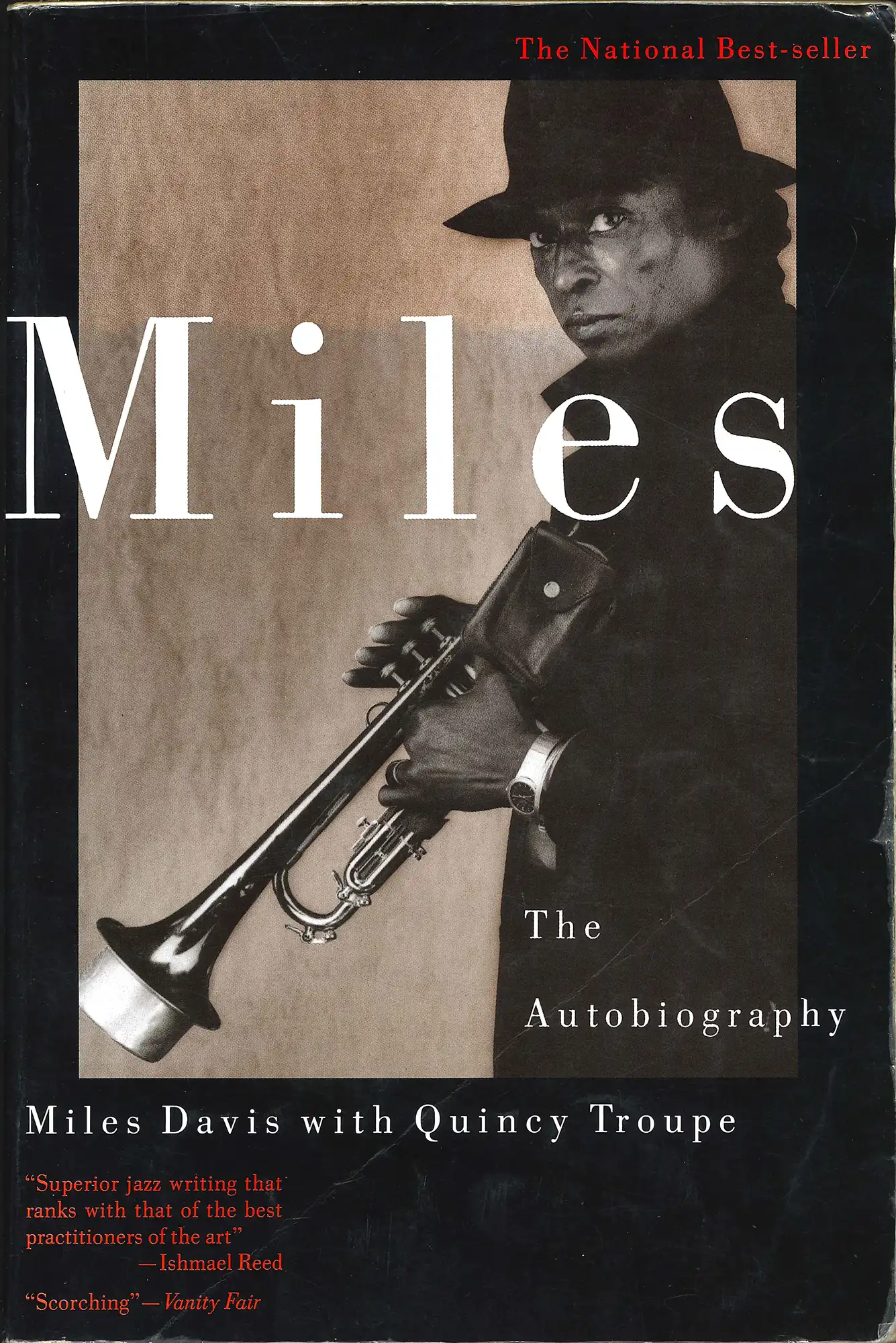

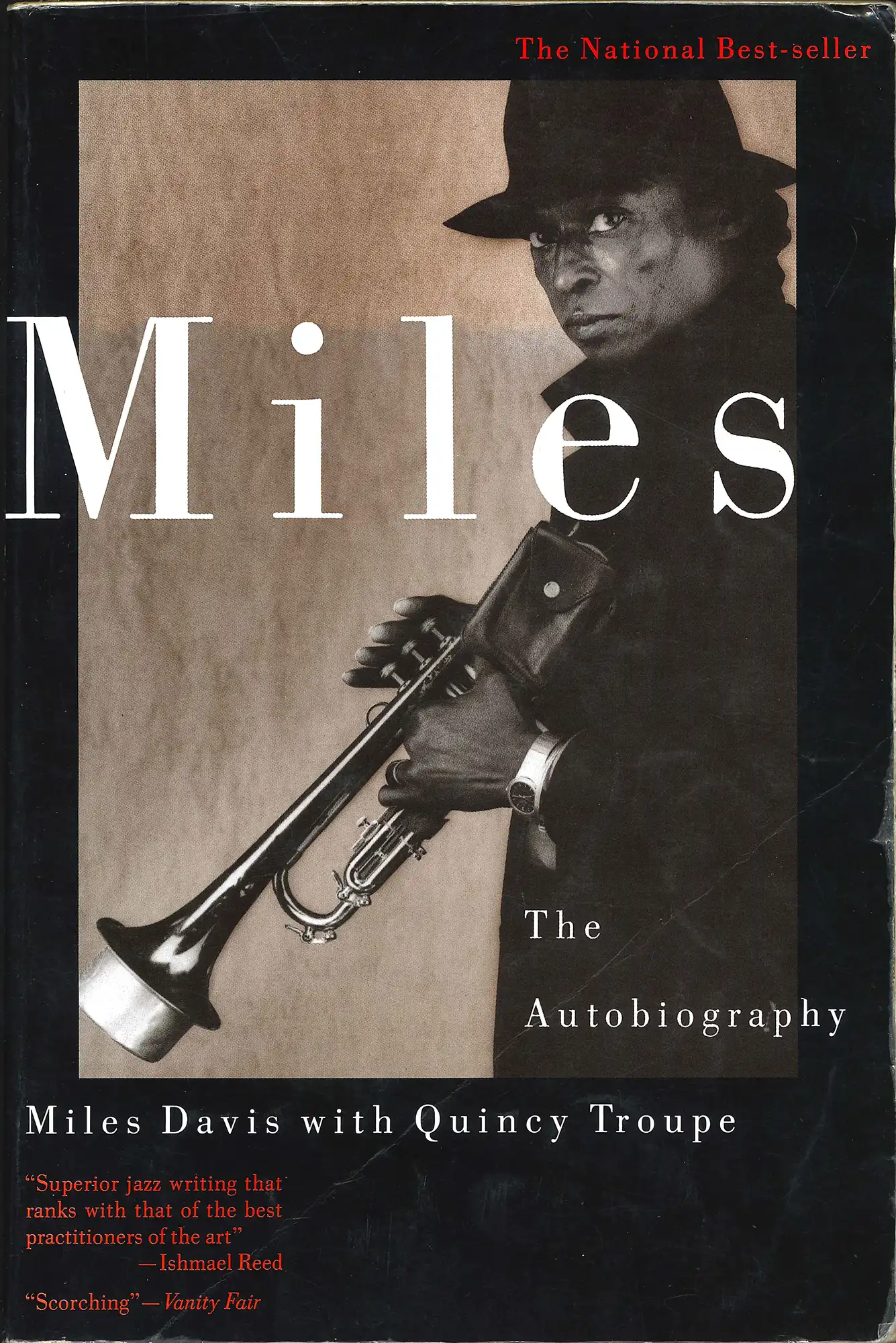

Miles Davis with Quincey Troupe, Miles: the autobiography. New York: Touchstone, 1989. SPRH 785.42092 DAV

Hotere often listened to music while he worked, and the small but eclectic collection of records included in his library reveal a sophisticated taste: American and South African jazz, classical, opera, dub and reggae and even a splash of comedy, in the form of a Fred Dagg album. He particularly favoured Miles Davis, perhaps especially after seeing him live in New York in 1986. The autobiography of Davis is one of only nine music-related books in his collection – about 1 per cent – but music was obviously important to him and the flow of his work.

Miles Davis with Quincey Troupe, Miles: the autobiography. New York: Touchstone, 1989. SPRH 785.42092 DAV

Open image in new window

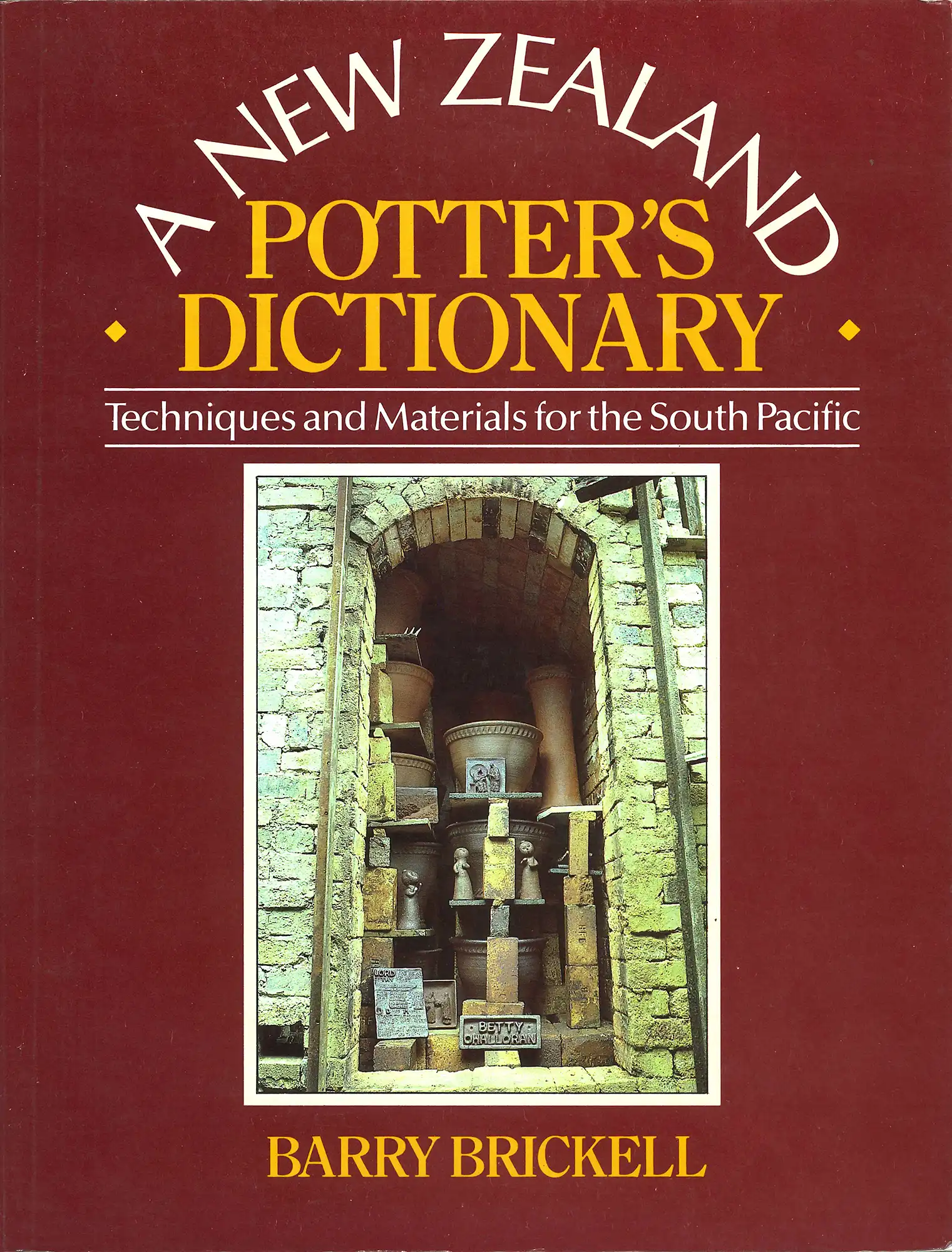

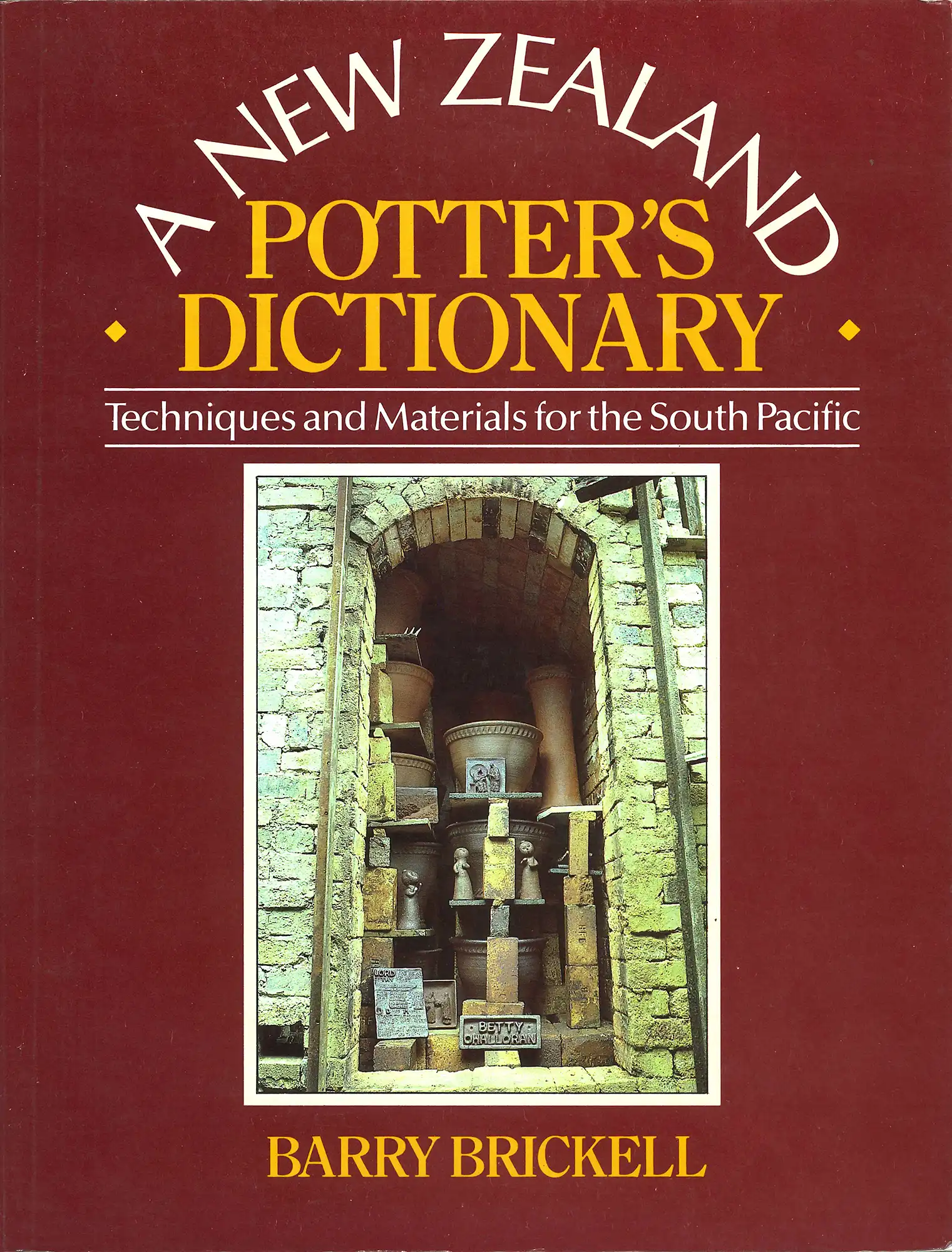

Barry Brickell, A New Zealand potter’s dictionary. Auckland: Reed Methuen, 1985. SPRH 738.103 BRI

When Hotere was an art adviser, he met Barry Brickell (1935-2016), one of the most important and colourful craft potters in New Zealand, when the latter was running workshops on kiln-making. They became good friends. Later, after supporting Brickell in his unsuccessful attempt at the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship, Hotere enticed him down to Dunedin anyway, to share his studio space and build a kiln. Brickell visited and worked in the studio over several years, and inspired Hotere enough to make ceramics of his own.

Barry Brickell, A New Zealand potter’s dictionary. Auckland: Reed Methuen, 1985. SPRH 738.103 BRI

Open image in new window

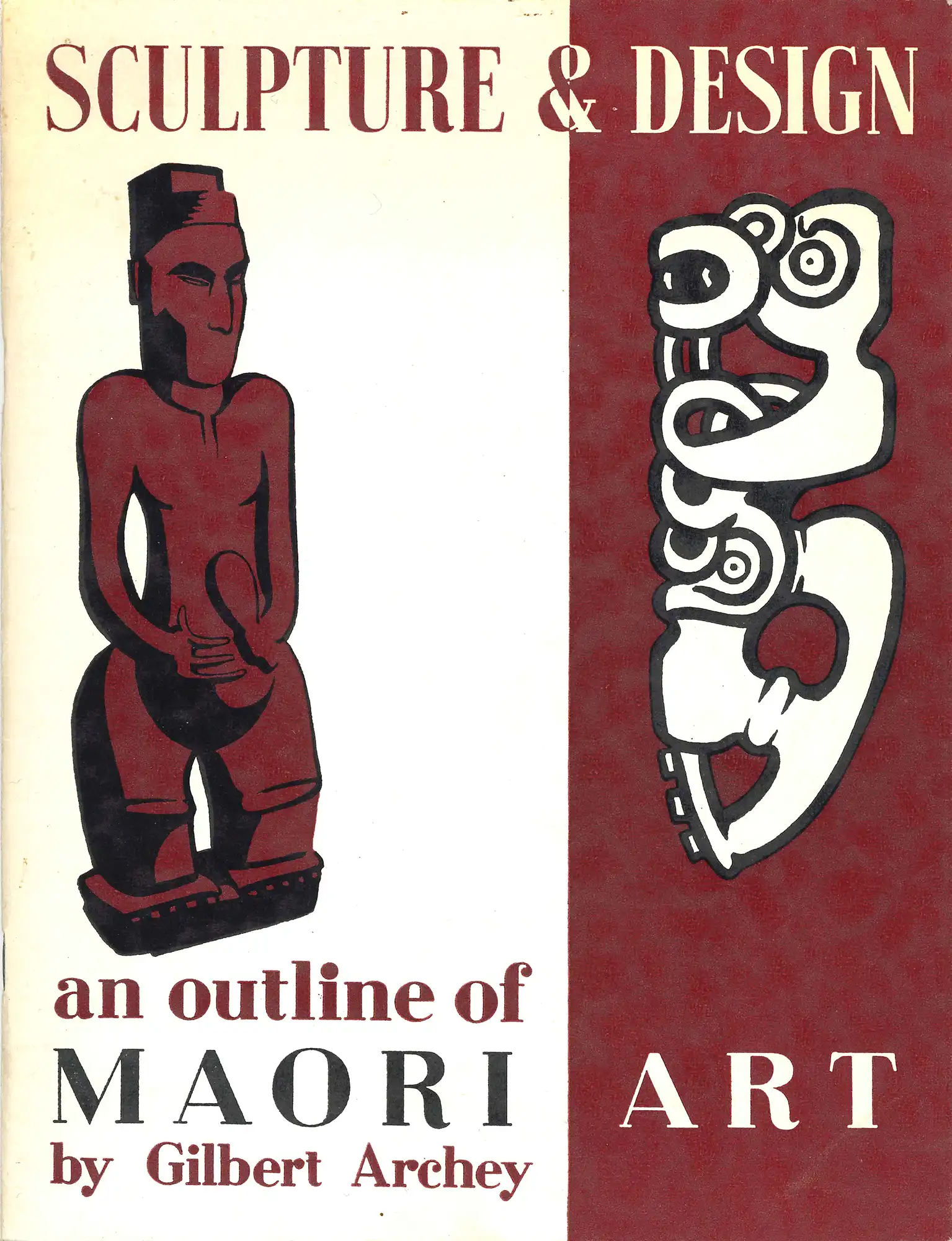

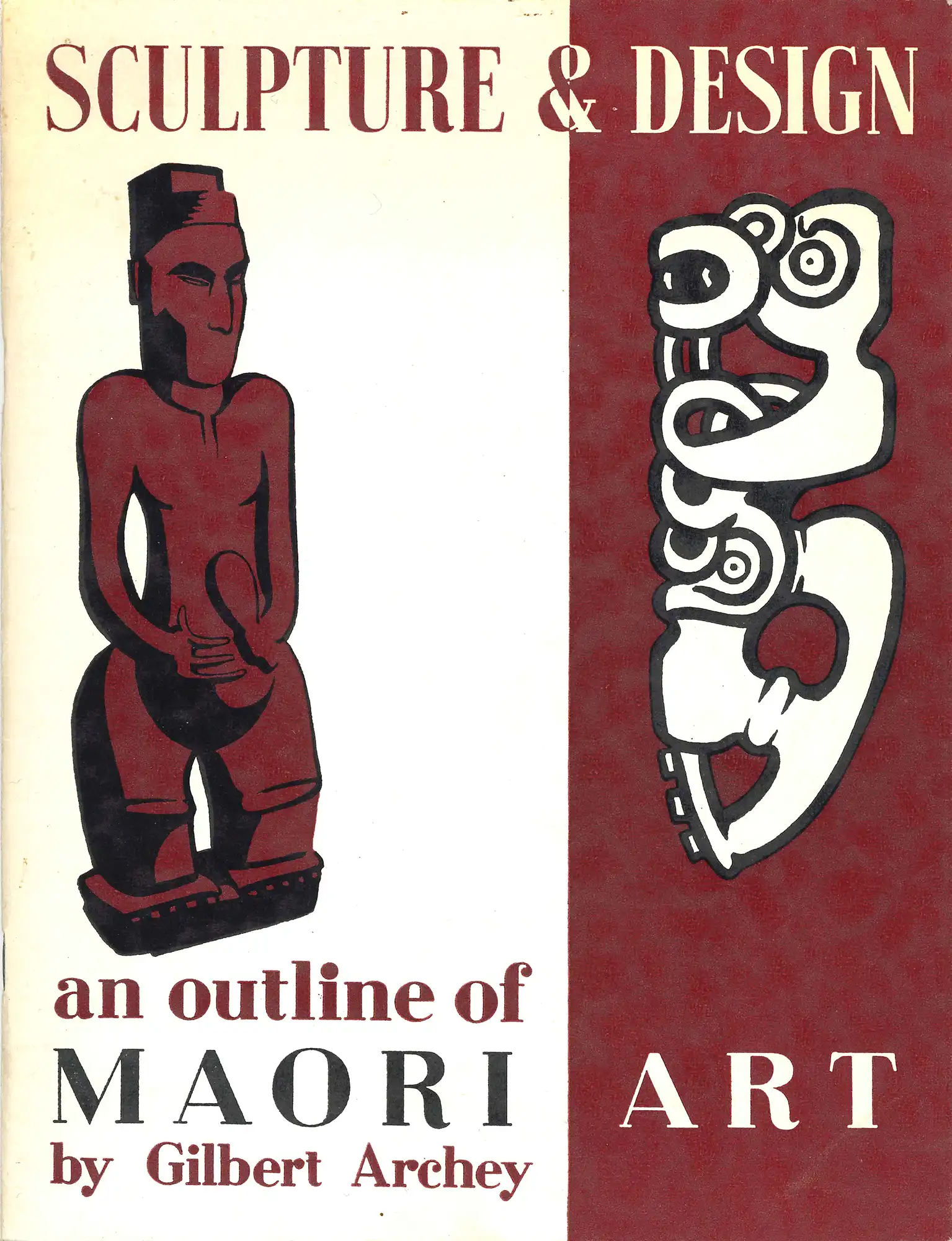

Gilbert Archey, Sculpture and design: An outline of Māori art. Auckland: Auckland War Memorial Museum, 1960. SPRH 736.40993 ARC

Hotere’s regular use of black in his works had multiple potential meanings, although he would confirm or deny none. The traditional Māori concept of te pō, for example, transcended predictable suggestions of night, darkness, and death in his work. He identified profoundly with his Māori heritage, but as a Māori artist, his label was much harder to define. In June 1973 he joined in the community of 200 Māori artists who met at the Te Kaha hui, convened by Hone Tuwhare. This immersion helped him to realise that he was not alone in eschewing the perceived necessary approval of the Pākehā art world, and he remained famously sceptical about the academic aspect of art history, appreciation, and criticism.

Gilbert Archey, Sculpture and design: An outline of Māori art. Auckland: Auckland War Memorial Museum, 1960. SPRH 736.40993 ARC

Open image in new window