Case 1

- Mainz: Gutenberg and Fust

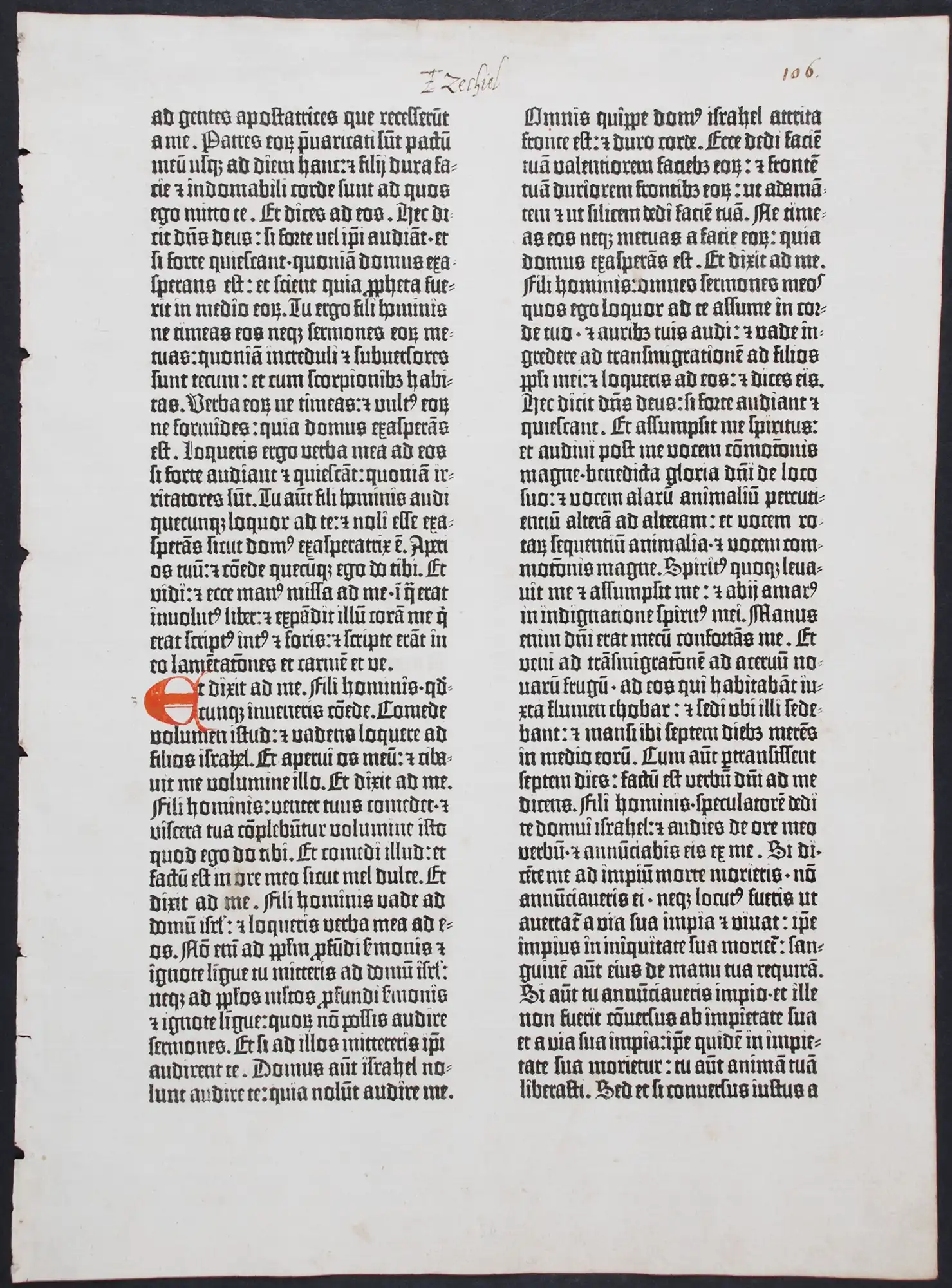

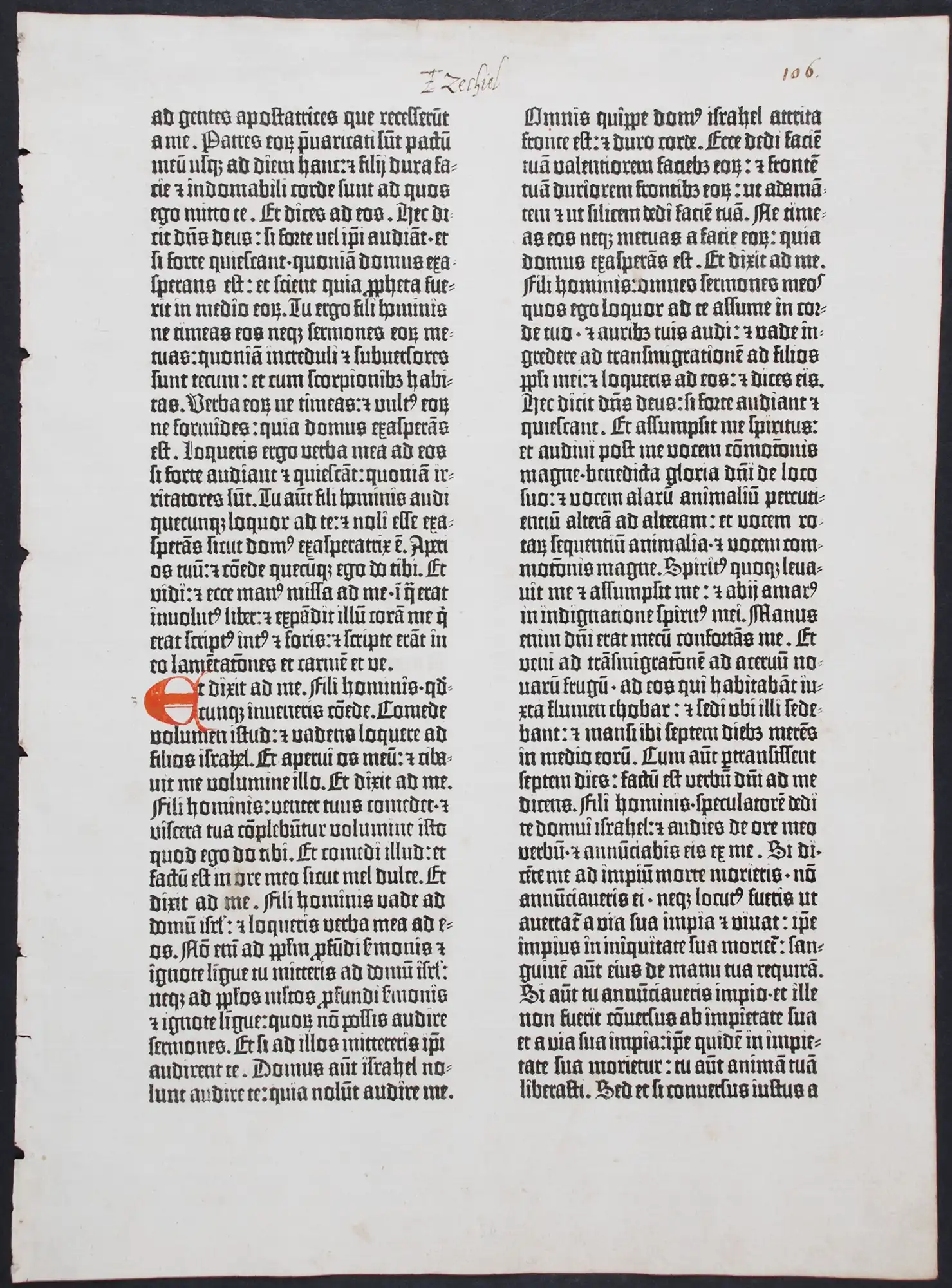

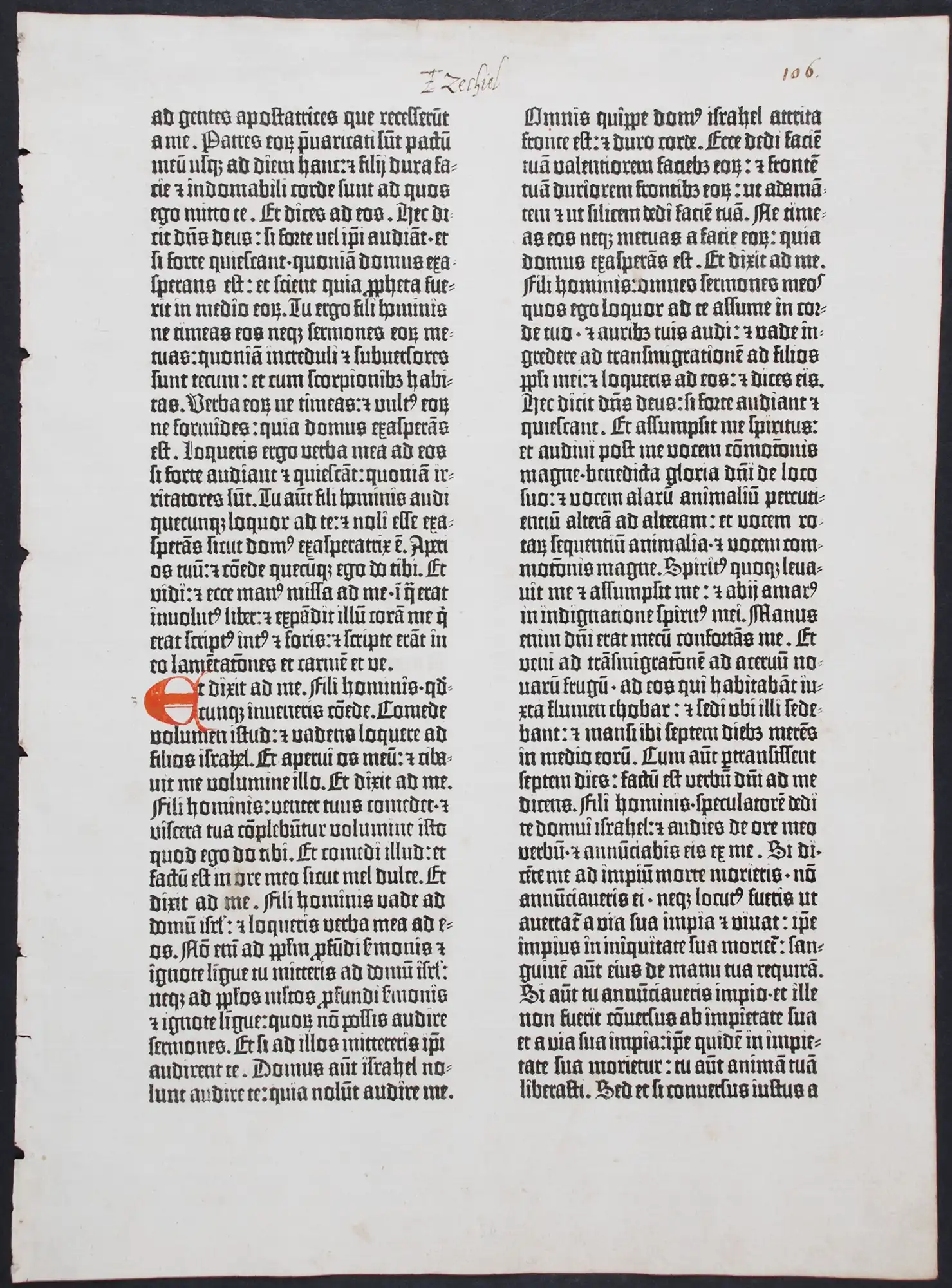

Bible. Latin Vulgate. Mainz: Johann Gutenberg and Johann Fust, ca. 1454. Single leaf. Part of Ezekiel 2:3-4:17.

The invention of printing with moveable type in the mid-fifteenth century is one of the most important developments in the history of western culture and civilisation. The printing of a Latin Bible (ca. 1455) by Johann Gutenberg (ca. 1399–1468) in Mainz, Germany, from a forme of metal type, marked the beginning of a process that scarcely changed in its essentials for 400 years.

Gutenberg’s great achievement was in bringing together and perfecting the combination of moveable type, printing ink, and a wooden screw-press to make printing from type (as opposed to using woodcut blocks) possible for the first time in Europe.

Gutenberg’s skills as a master goldsmith allowed him to create the first sets of metal typefaces, which were modelled on contemporary manuscript letterforms. Indeed, early printed books mirrored their manuscript counterparts in form and layout. The chief advantage of the printing press over manuscript production was its ability to produce in a short period of time many identical copies of any given work. This led to the rapid dissemination of knowledge, to the forming of new communities of learning and scholarship, and eventually to the literate mass culture we know today.

Modern scholarship suggests that Gutenberg’s Bible was produced in an edition of 180 copies – 135 on paper and about 45 on vellum. Less than fifty, in various states of completeness, survive to the present day: thirty-six on paper and twelve on vellum.

Bible. Latin Vulgate. Mainz: Johann Gutenberg and Johann Fust, ca. 1454. Single leaf. Part of Ezekiel 2:3-4:17.

Open image in new window

![Giovanni Balbi. Catholicon. Latin. Mainz: [Johann Gutenberg?], 1460. Single leaf. Dictionary entries beginning recto](https://www.reedgallery.co.nz/exhibitions/the-glory-of-print/1/1b.webp)

Giovanni Balbi. Catholicon. Latin. Mainz: [Johann Gutenberg?], 1460. Single leaf. Dictionary entries beginning recto "Fartu[m]" and ending verso "Fatuus".

In about 1450, Gutenberg formed a partnership with the wealthy Johann Fust, and began the production of his 42-line Bible. According to a document known as the Helmasperger Instrument (6 November 1455), a lawsuit was brought by Fust against Gutenberg for monies owed. The funds were most likely instrumental in the development of Gutenberg’s printing press, which was probably modelled after large screw presses used for making wine. The court evidently decided in Fust’s favour, and it is presumed that Gutenberg was ordered to give up some or all of his printing equipment in the verdict (Fust went on to establish a successful printing shop with the partnership’s leading assistant, the calligrapher Peter Schöffer).

Approximately five years later, Gutenberg formed a new partnership with the lawyer Conrad Humery. In 1460, an edition of the Catholicon (a Latin dictionary) was published in Mainz. While Gutenberg’s name is suggested as its printer, there is debate as to whether he was involved in printing the Catholicon (or anything else) after the 1450s.

In 1465, Gutenberg was granted a pension as a courtier of the prince-archbishop of Mainz, which kept him from want. He died in February 1468 and was buried in a Franciscan church. The church, along with Gutenberg’s grave, were destroyed in the Siege of 1793. Although Gutenberg’s name was little known after his death, the rediscovery of specimens of his 42-line Bible during the eighteenth century has led to worldwide admiration and interest in his invention.

![Giovanni Balbi. Catholicon. Latin. Mainz: [Johann Gutenberg?], 1460. Single leaf. Dictionary entries beginning recto](https://www.reedgallery.co.nz/exhibitions/the-glory-of-print/1/1b.webp)

Giovanni Balbi. Catholicon. Latin. Mainz: [Johann Gutenberg?], 1460. Single leaf. Dictionary entries beginning recto "Fartu[m]" and ending verso "Fatuus".

Open image in new window

![Giovanni Balbi. Catholicon. Latin. Mainz: [Johann Gutenberg?], 1460. Single leaf. Dictionary entries beginning recto](https://www.reedgallery.co.nz/exhibitions/the-glory-of-print/1/1b.webp)