Case 3

- The Pickwick Papers

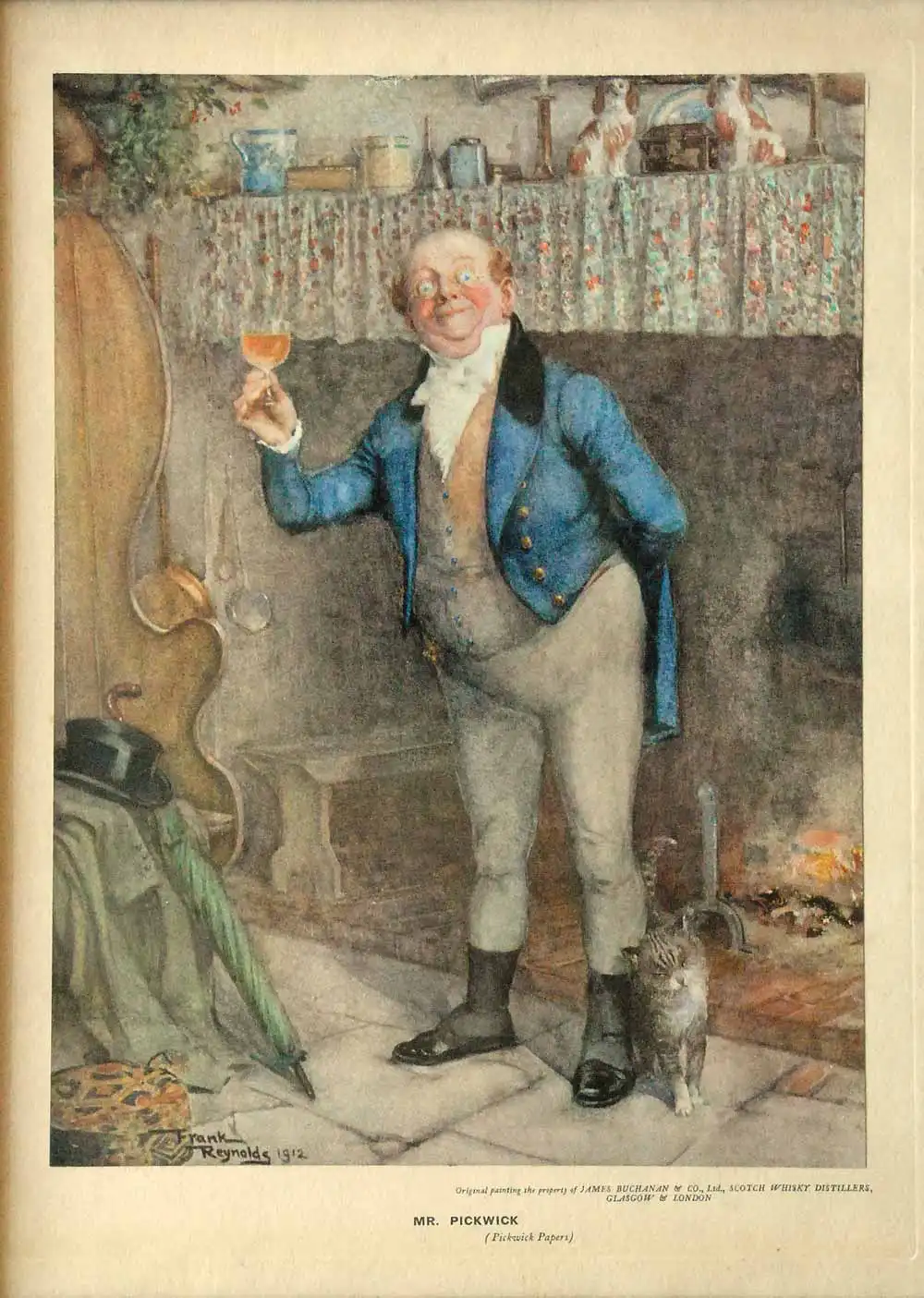

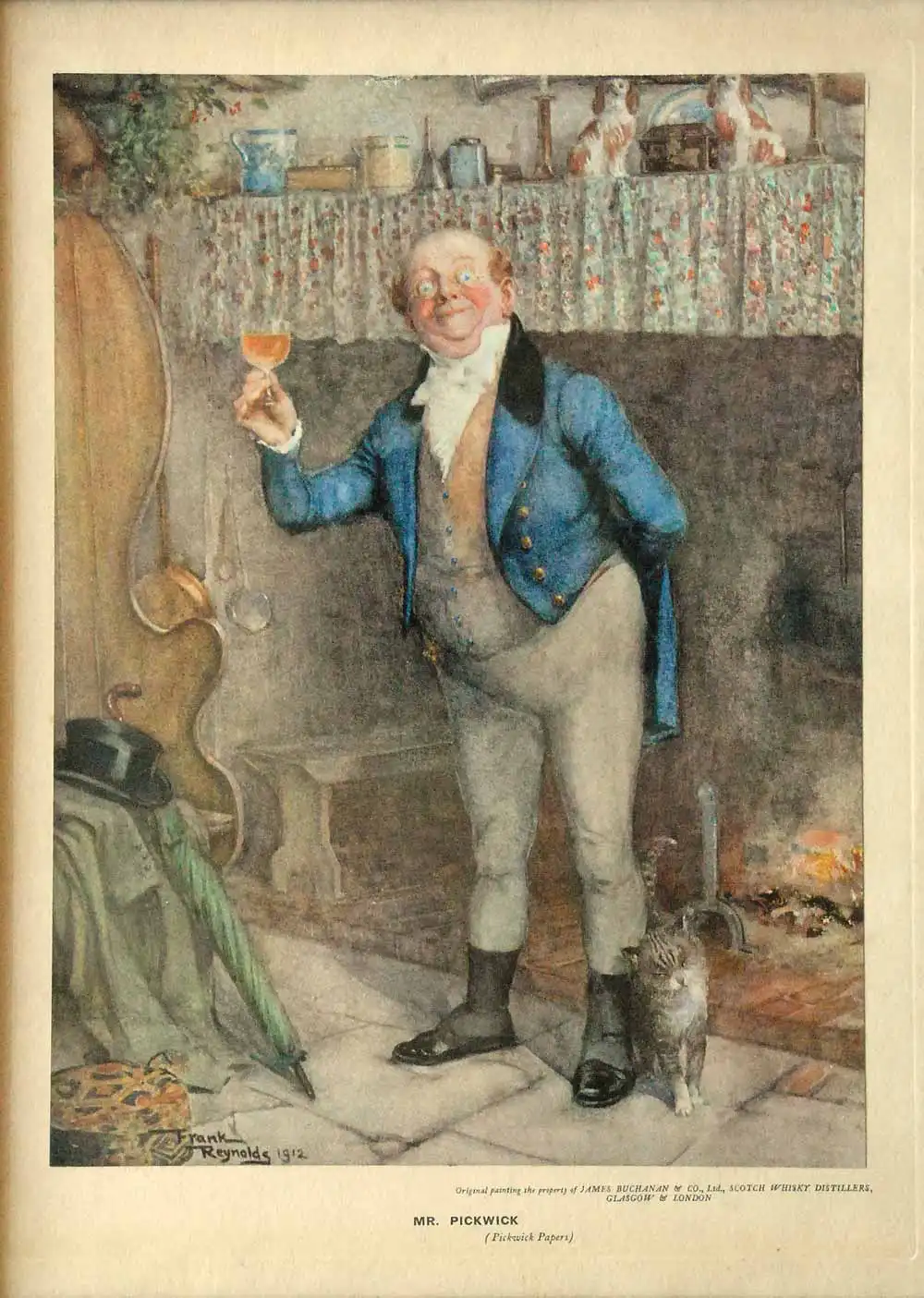

Framed reproduction of Frank Reynolds’s painting of Mr. Pickwick, 1912.

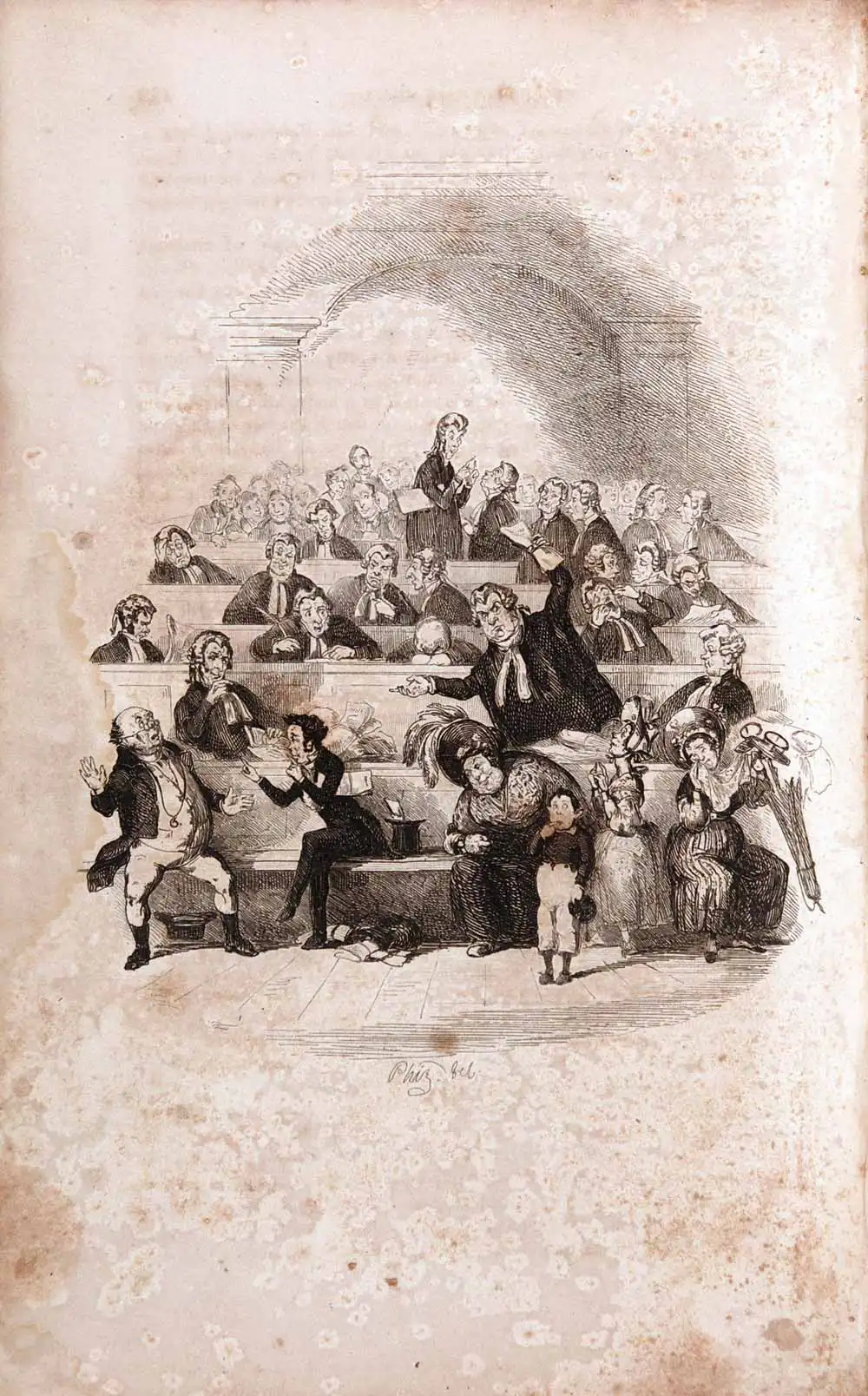

The publishers Chapman and Hall, who bought the rights to Sketches from Macrone, wanted an author to write the text to accompany some humorous, burlesque sketches by the well-known artist Robert Seymour (1798–1836). The drawings were of the misadventures of a group of Cockney sportsmen, to be called the “Nimrod Club”. Chapman and Hall, impressed with the talent exhibited in Sketches, approached Dickens. He accepted, but insisted on far more control than they intended, and gradually the work became his rather than Seymour’s. The club name was changed to the “Pickwick Club”, and the text, not the illustrations, became dominant.

The first issue appeared in April 1836. Unfortunately, Seymour committed suicide shortly thereafter. A new artist had to be found. The job eventually went to the then unknown Hablot Knight Browne (1815–82), who was to illustrate Dickens’s works for the next thirty years. He even took on the nickname “Phiz”, to complement Dickens’s “Boz”.

Pickwick became an overwhelming triumph. Approximately 40,000 copies were in circulation at the end of its serial run, and its success encouraged Dickens to adopt the monthly-number format as standard practice.

![Letter (in third person). Charles Dickens to E. Hill, 48 Doughty Street, London, [early December 1837]](https://www.reedgallery.co.nz/__data/assets/image/0018/235710/case3-item3.webp)

Letter (in third person). Charles Dickens to E. Hill, 48 Doughty Street, London, [early December 1837]

This delightful depiction (complete with adoring feline) is of Samuel Pickwick, the main protagonist in Dickens’s novel and founder of the Pickwick Club. “Names”, wrote Peter Ackroyd, “would always be very important to [Dickens]. In later years he could not begin a book until he had hit upon the right title, and … he made lists of fanciful or odd surnames to assist with his inspiration”.

The inspiration for the name of the title character in Pickwick was one Moses Pickwick (1801–58), the proprietor of a coach company that journeyed between Bath and London which Dickens no doubt used while travelling as a reporter. As for the character of Samuel Pickwick, he is, in the words of Michael Slater, “rather like one of those prosperous, self-satisfied old bachelors, often with a hobby-horse, who figure in some of the Monthly tales”; a plump, amiable fellow with “beaming” and “twinkling” eyes.

The artist, Frank Reynolds (1876–1953), was art editor for Punch magazine and became known for illustrating a number of Dickens’s works.

![Letter (in third person). Charles Dickens to E. Hill, 48 Doughty Street, London, [early December 1837]](https://www.reedgallery.co.nz/__data/assets/image/0018/235710/case3-item3.webp)

Letter (in third person). Charles Dickens to E. Hill, 48 Doughty Street, London, [early December 1837]

Open image in new window

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club … with Forty-Three Illustrations by R. Seymour and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, 1837; first edition

By December 1837, Dickens and his family had taken up residence in 48 Doughty Street, in the London district of Camden Town. Charles and Catherine lived there with the three eldest of their eventual ten children, Dickens’s younger brother Frederick, and his sister-in-law, Mary.

The two years that Dickens lived in the house were very productive. He not only completed The Pickwick Papers, but also wrote the whole of Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby, and began Barnaby Rudge. When his income increased, Dickens moved his family to a grander residence. 48 Doughty Street, once slated for demolition, is now the Charles Dickens Museum.

The “little boy” mentioned in this letter was Charles, Jr., who was then just shy of his first birthday. On 11 December 1837 Dickens informed John Forster that his son had measles, so it would appear that the letter was written at about that time.

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club … with Forty-Three Illustrations by R. Seymour and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, 1837; first edition

Open image in new window

![Letter (in third person). Charles Dickens to E. Hill, 48 Doughty Street, London, [early December 1837]](https://www.reedgallery.co.nz/__data/assets/image/0018/235710/case3-item3.webp)