Case 5

- Authors’ Presentation Inscriptions 3

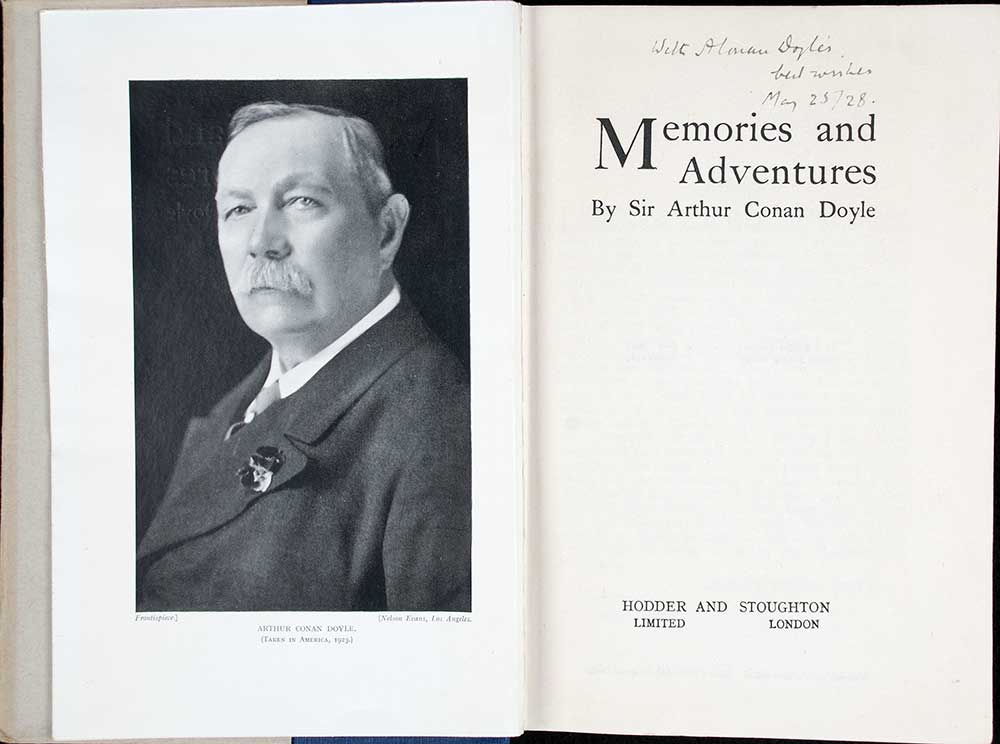

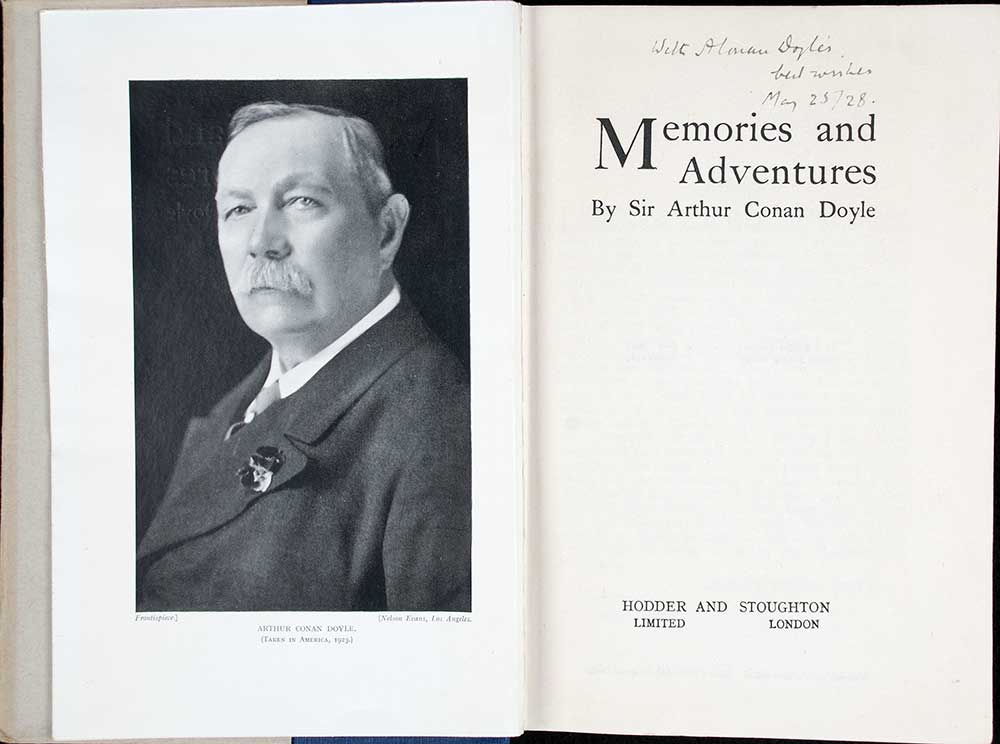

Arthur Conan Doyle. Memories and adventures. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1924.

This

copy of Conan Doyle’s Memories and

adventures with his signed inscription was sent to A.H. Reed, as he recalls

in his 1969 autobiography:

“About 40 years ago I found, in a

miscellaneous parcel of letters, a very personal one written by the novelist as

a young man to his mother … With a desire to do as I would have liked to be

done by, I wrote to Sir Arthur telling him I would send him the letter if

desired. I received a reply from his secretary (perhaps he suspected I merely

wanted his own autograph) stating that he would be glad to receive it, and that

in acknowledgement he would send me several letters of eminent people. I

replied, sending his mother’s letter, and stating that all I wanted was a

replacement letter of his own. He did not reply, nor send me the letters he had

promised; perhaps he thought the inscribed Memories and adventures would please me more.”

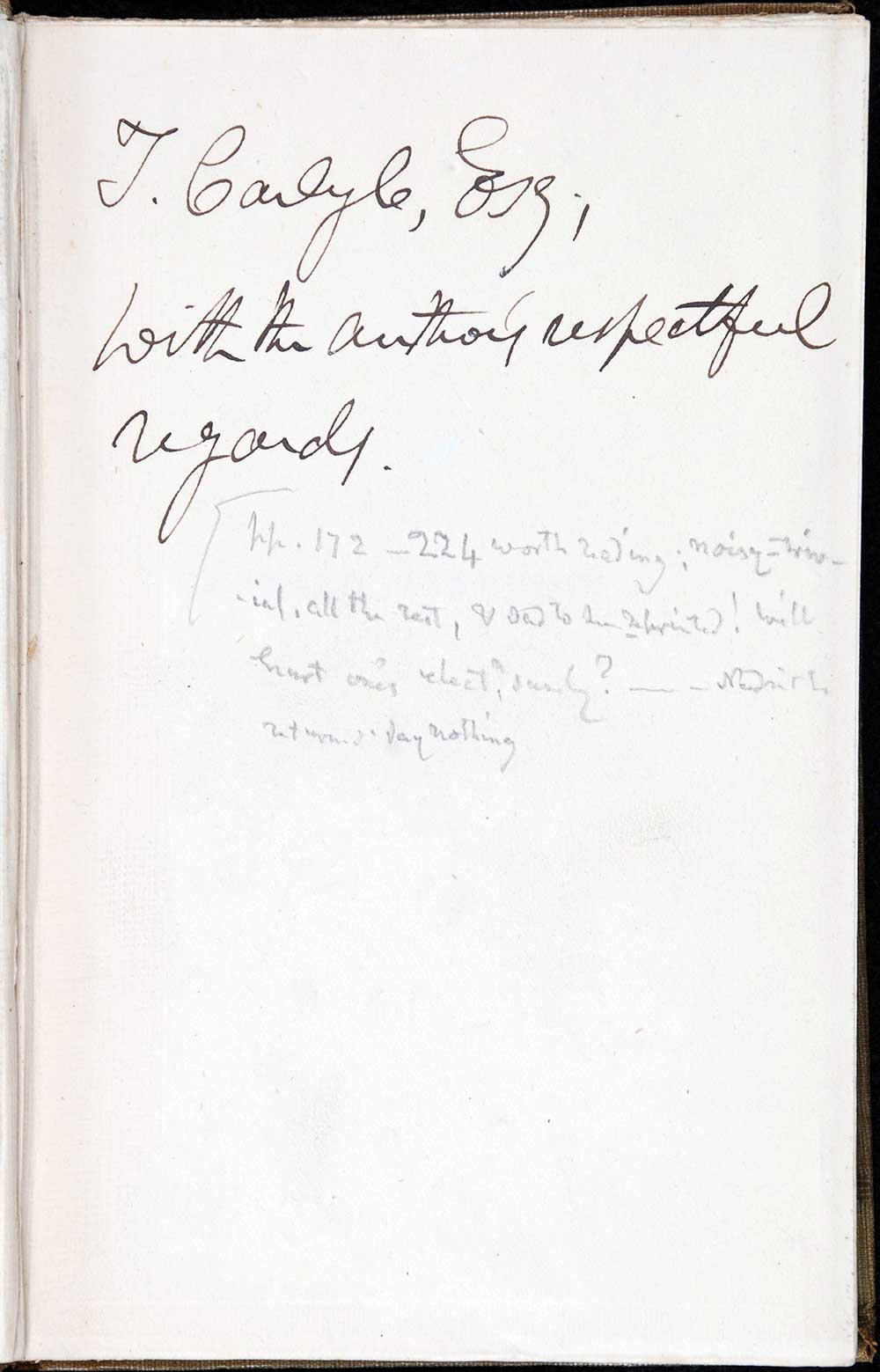

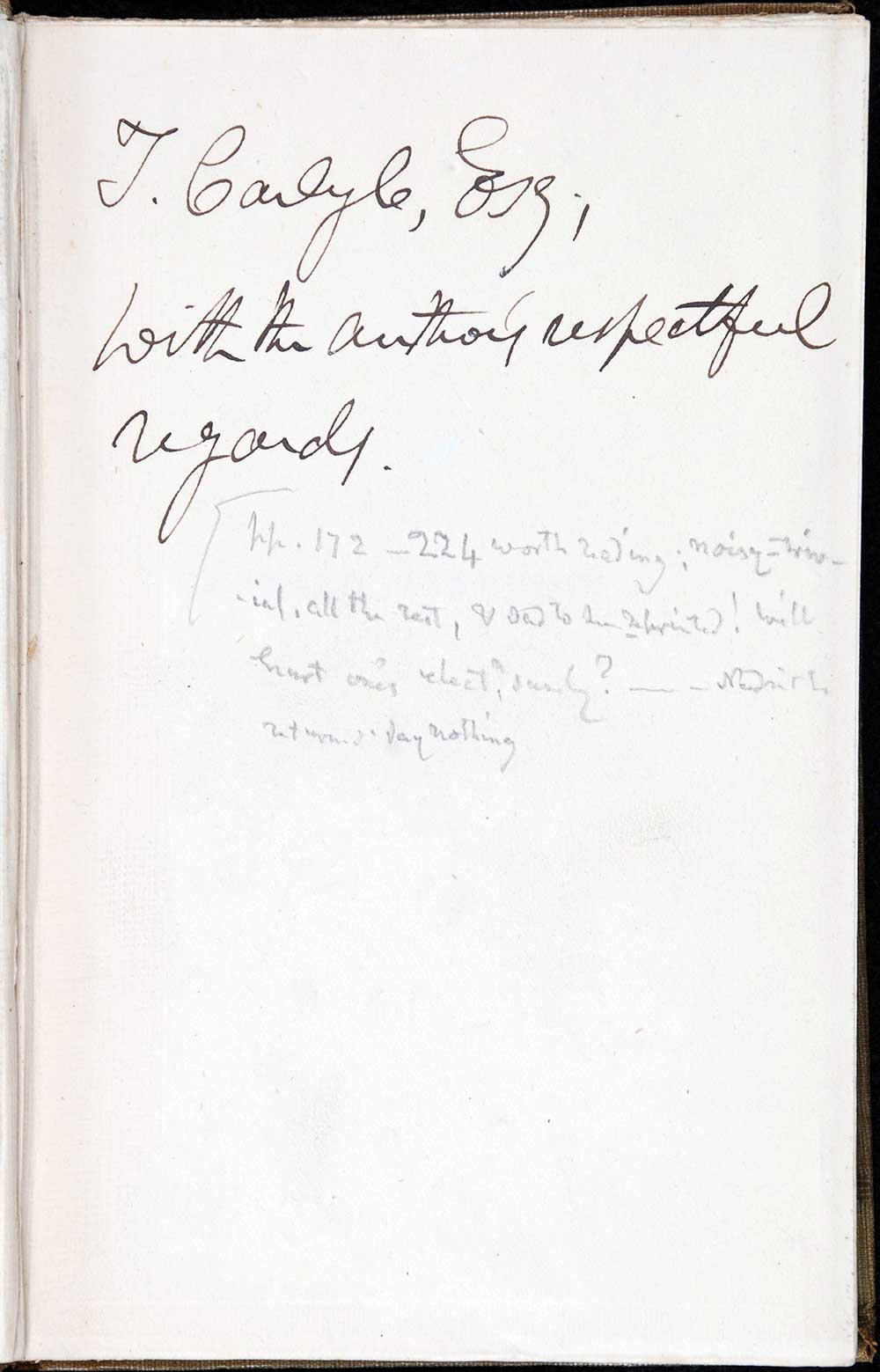

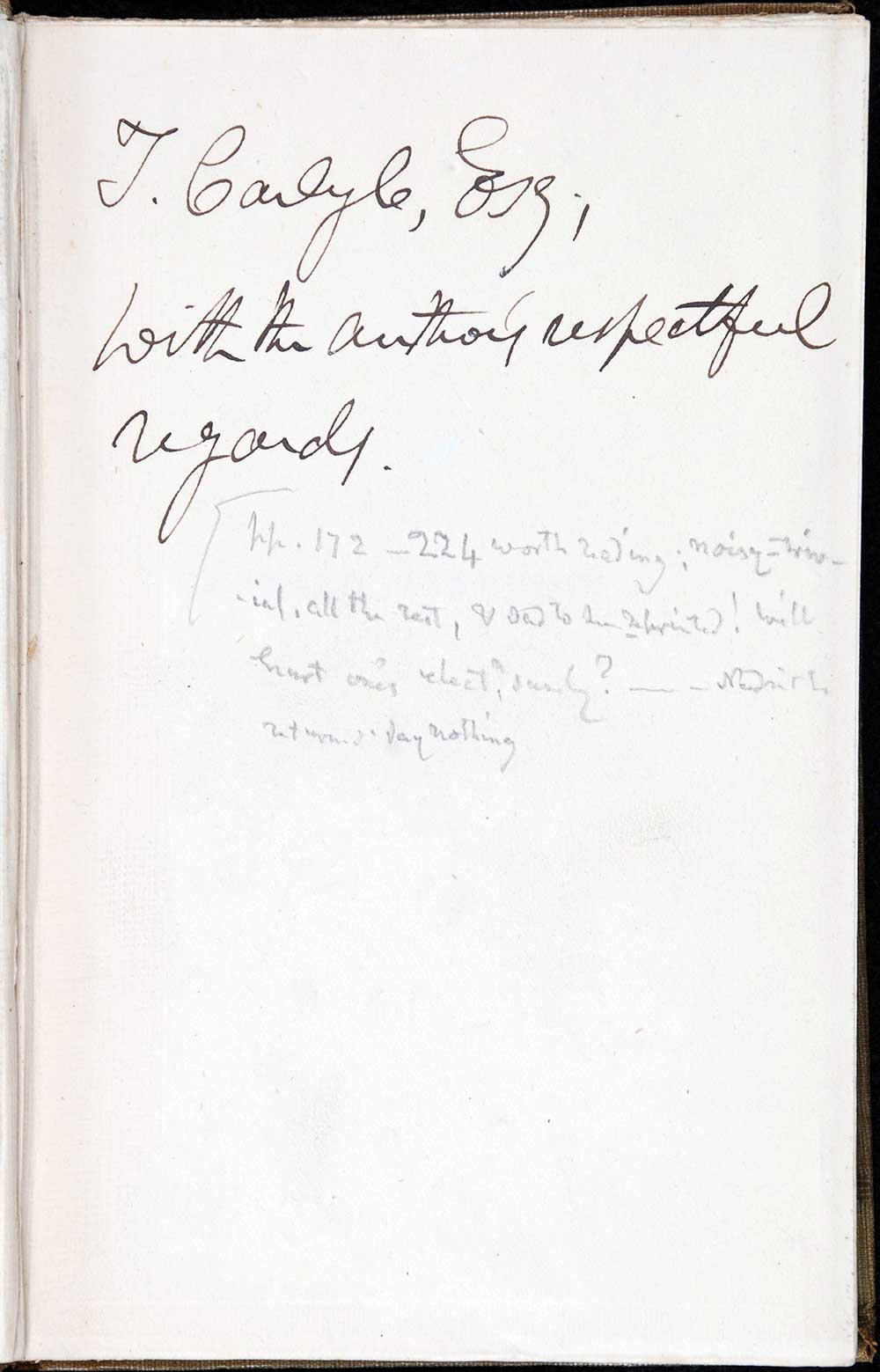

James Hutchison Stirling. Jerrold, Tennyson and Macaulay: with other critical essays. Edinburgh: Edmonston & Douglas, 1868.

This

presentation copy was sent by the author, the Scottish philosopher James

Hutchison Stirling (1820-1909) to the eminent biographer and historian Thomas Carlyle

(1795-1881).

The Oxford dictionary of national

biography

describes Stirling as ‘an ardent admirer of Carlyle … [who] corresponded with

the sage as early as 1842, mimicked his passionate style, adopted his cultural

pretensions, and took his advice to learn French and German as a means to

mastery over contemporary European literature and philosophy.’

Beneath

the inscription are pencilled notes in Carlyle’s hand. Though he found pages

172-224 ‘worth reading’ it appears Carlyle found much of the rest of Stirling’s

text to be ‘noisy - trivial.’

James Hutchison Stirling. Jerrold, Tennyson and Macaulay: with other critical essays. Edinburgh: Edmonston & Douglas, 1868.

Open image in new window

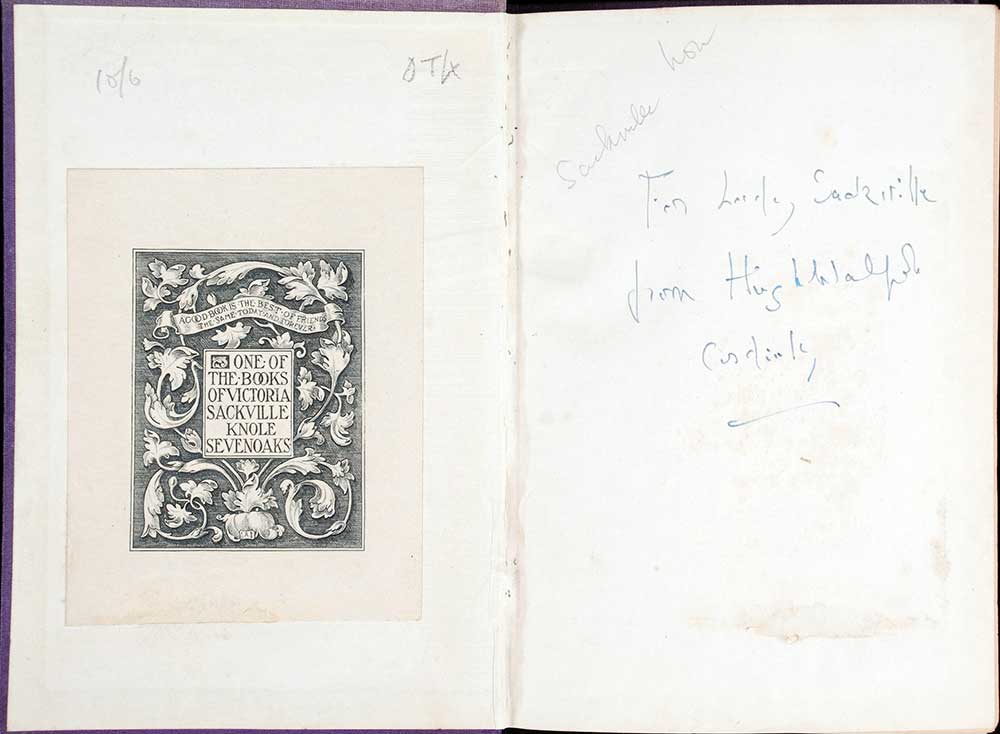

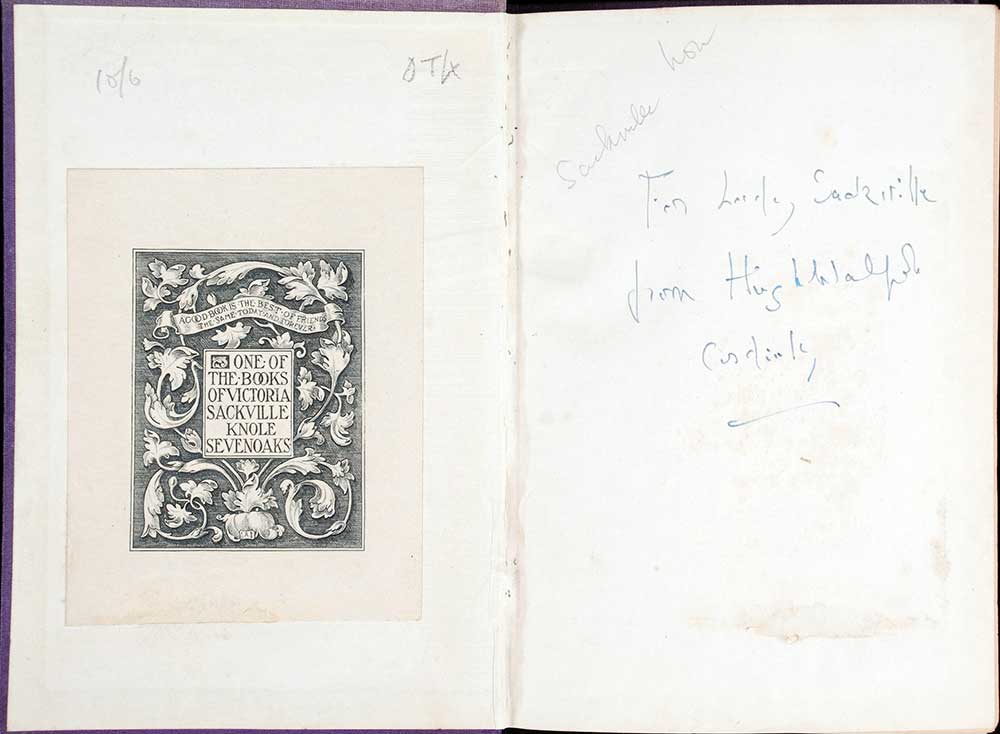

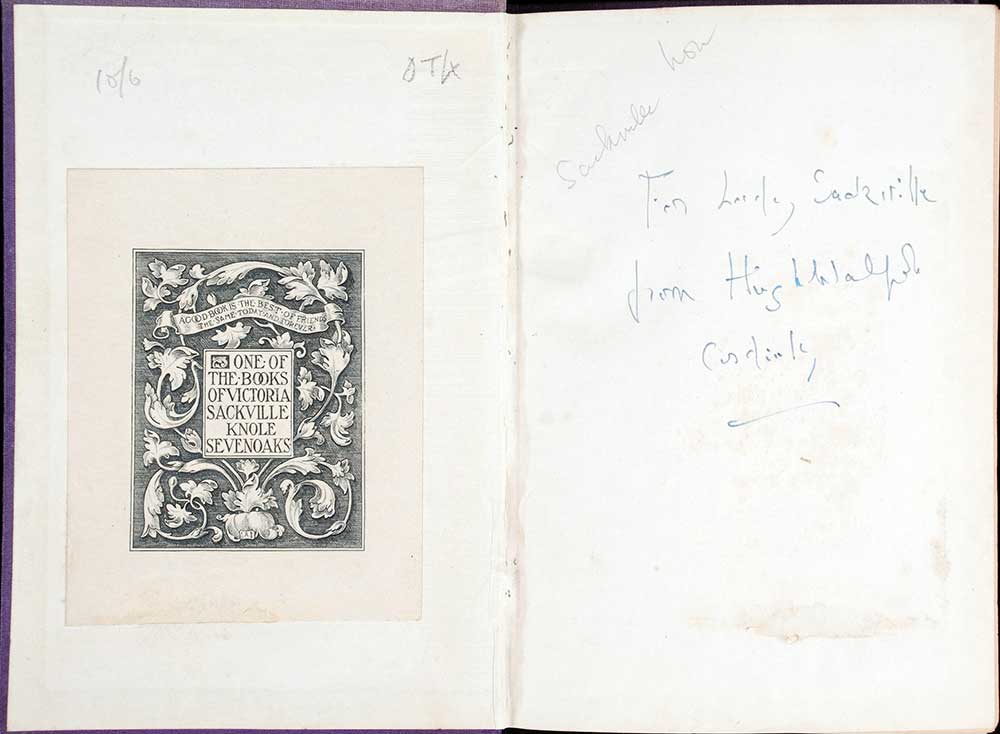

Hugh Walpole. Fortitude: being a true and faithful account of the education of an explorer. London: M. Secker, 1916.

The Reed

copy of the early Hugh Walpole novel Fortitude

contains the author’s presentation inscription “to Lady Sackville” on the

flyleaf, with the bookplate of Victoria Sackville of Knole House affixed to the

front pastedown.

The

recipient of Walpole’s gift was Victoria Sackville-West, Baroness Sackville

(1862-1936). Victoria was the illegitimate daughter of the English diplomat,

Lionel Sackville-West, 2nd Baron Sackville, and a Spanish dancer.

Victoria married her cousin, Lionel Edward Sackville-West, 3rd Baron

Sackville. Although an animated figure herself, Victoria’s life has been

overshadowed by that of her daughter, who bore the same name.

Victoria,

usually known as Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962), was a colourful figure with

whom Walpole was well acquainted. Vita was a successful novelist, poet and

journalist, as well as an eminent garden-designer. She is also remembered as

the inspiration for the androgynous protagonist of Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando.

Hugh Walpole. Fortitude: being a true and faithful account of the education of an explorer. London: M. Secker, 1916.

Open image in new window